Industry insights on skills needs

The Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC's 2019 Skills Forecast states that the top generic skills for the Aquaculture and Wild Catch industry range from learning agility and information literacy, through to communication and virtual collaboration skills, language, literacy and numeracy (LLN), and managerial and leadership skills. Technology is rated as the fifth most important generic skill for the industry.

The Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC's 2019 Skills Forecast identifies a range of significant challenges that impact on the uptake and implementation of industry training, including:

- Declining and ageing workforce

- Attracting and recruiting young people

- Restrictions on visa programs for skilled migration

- Limited options for subsidised training

- Geographical and regional dispersion of businesses

- Limited access to registered training organisations (RTOs)

- Competing industries

- Regulation and licensing implications.

The key priority skills identified by the Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC that will require future projects are:

- Development of the crocodile farming market

- Increased use of FishTech and Aquabotics in operations

- Development of partnerships with traditional owners for industry operations

- Potential development of Indigenous enterprises related to aquaculture and wild catch, including customary fishing.

Crocodile farming is an expanding opportunity in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland. The challenges of crocodile farming are unique in that it involves one of the world's oldest and most dangerous predators and, while risks may be minimised, there are potentially fatal consequences for both workers and animals. There has been significant growth in crocodile farming and associated markets based on crocodile skins, meat, by-products, tourism and conservation.

Park rangers, zoo employees, crocodile farm workers, and licenced individuals all need the same foundational skills to work with crocodiles and their eggs in ways that are safe and sustainable. This requires knowledge of diseases, biosecurity management, and the humane treatment of crocodiles, as well as the ability to perform risk assessment and an understanding of cultural sensitivities relating to Indigenous communities. Additional expertise is also needed depending on whether animals are in the wild or in a controlled environment.

Working with crocodiles is a complex field, overlapping a number of sectors including conservation and land management, animal care and management, and aquaculture. It is also closely tied to Indigenous communities, who have respected crocodiles as entities and a source of food for thousands of years. Crocodile farming and conservation in particular utilises Indigenous knowledge and provide economic benefits for Traditional Owners through employment and royalty payments for egg collection on their land.

During 2019 and 2020, the Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC oversaw the Work With Crocodiles Project. Key outcomes of the project included:

- The Certificate III in Working with Crocodiles was developed.

- Eight skill sets were developed: Introduction to Working with Crocodiles, Care for Crocodiles in a Controlled Environment, Hatchling and Juvenile Crocodile Care, Crocodile Egg Harvesting, Crocodile Relocation, Crocodile Incident, Crocodile Survey and Crocodile Public Relations.

- Eleven units of competency specifically focused on working with crocodiles and working in crocodile habitats were developed. All of which are featured as core and elective units in the Certificate III in Working with Crocodiles, within the SFI Seafood Industry Training Package.

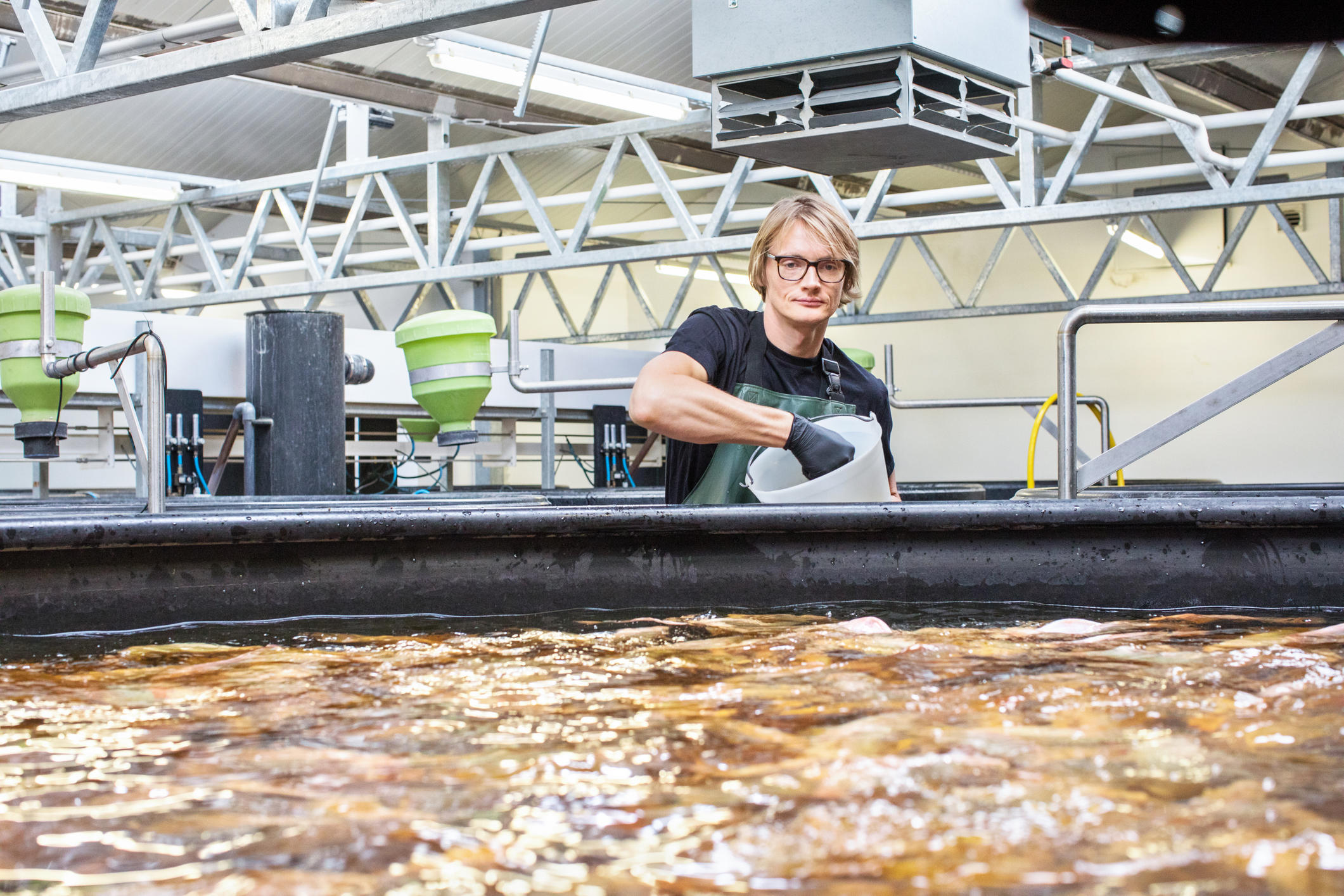

New underwater technologies, such as Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), underwater drones and biosensors, are changing the way work is done in Australia's aquaculture industry. From monitoring fish health and environmental conditions, to inspecting and repairing nets, many job tasks that were previously done manually can now be performed remotely. These are important advancements, improving productivity, catch sustainability, environmental control, stock and habitat welfare, and biosecurity. It is expected that these developments will affect most job roles, as uptake of these new technologies becomes more widespread, requiring updated skills in digital literacy, data, automation and environmental sustainability.

During 2019 and 2020, the Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC oversaw the Fishtech and Aquabotics Project. Key outcomes of the project included:

- Three new skill sets were developed for aquatic technology induction, aquabotics and aquatic environmental audit.

- Nine new units of competency were developed, with a focus on the use and future use of technology in the Seafood industry. These units will be incorporated as electives into existing aquaculture qualifications, in addition to being available for import to other qualifications. Some units have been developed to meet immediate needs and others are intentionally generic to future proof them and allow for new and emerging technologies to be incorporated into training.

- Twenty-three units of competency were revised so that they are applicable for use in the context of remote technologies.

The Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC’s 2020 Skills Forecast highlights skill needs around industry leadership and succession planning. Several Seafood Industry Training Package qualifications are intended for job outcomes in leadership and management roles. As the Seafood industry has an ageing workforce and is struggling to attract the next generation of workers, the perceived importance of these qualifications will likely be enhanced as succession planning becomes increasingly vital for the continuation of operations.

The Aquaculture and Wild Catch IRC’s 2021 Skills Forecast states that the past year was turbulent and unpredictable for the aquaculture, fishing and seafood sector due to a combination of the impacts of COVID-19, changes to international markets and the continuing evolution of the Australian industry. The IRC monitored the performance of the updated SFI Seafood Industry Training Package throughout 2020 and determined that the training package, along with the updates related to the use of technology and working with crocodiles, is a robust, up-to-date set of industry skill standards with the flexibility and content needed to meet industry needs. Research to date has shown no skills gaps in the skills standards.

Increasingly apparent is that the ability of the industry to attract workforce is the biggest barrier to training, as competition for workers continues to grow. In particular, the revitalisation of the mining industry in Western Australia is attracting labour to the detriment of other industries. With a lack of access to migrant and visa workers as a result of the pandemic, employers are finding it increasingly difficult to find the workers needed. The IRC found no evidence of a reluctance to train workers by employers, or a lack of willingness of governments to fund training (although mainly for qualifications).

In planning for its future workforce, as the industry grows and evolves, the Tasmanian Seafood Industry Council (TSIC) recognises that it needs to shift its mindset to better understand the needs of the next generation of workers so that they can attract, train, support and retain a productive, reliable and committed workforce. The Next Generation: Tasmanian Seafood Industry Workforce report argues that the opportunity, and challenge, for the Seafood industry to attract a future workforce in a competitive Tasmanian labour market is to better understand the needs and expectations of the new generation of seafood workers; their strengths, motivations, skill requirements and career aspirations and then respond to those needs so that both the industry and future workforce can benefit over the longer term. The Seafood industry must also balance the new workforce needs with its own current challenges such as regionality, isolation, pay and labour shortages.

The Victoria's Fisheries and Aquaculture: Economic and Social Contributions report examines how the Seafood industry contributes to the types and nature of employment opportunities in regional communities. Seafood production adds to the diversity of economic opportunities, which is critical for economic resilience in regional towns, especially in places where there are few alternative industries and where it can alleviate dependence on large sectors and companies. Fishing and aquaculture contributes to the economic stability of communities because they provide a year-round baseline of activity, which keeps local regional economies 'ticking over' when other industries (e.g., tourism) operate seasonally or intermittently. The diversity of jobs in fisheries and aquaculture production, the diversity of business types that provide inputs into production, and the diversity of post-harvest businesses, including those jobs associated with transport, processing, wholesaling, and retailing Victorian seafood, are considered. Key findings include:

- Employment in seafood production requires a diverse and often high-level specific skillset, but also provides entry-level jobs.

- The Seafood industry provides jobs for people who might find it difficult to get work elsewhere, people who may have struggled in life, or who may not easily fit into mainstream life.

- There are opportunities for young people to enter the Seafood industry. However, the professional fishing industry struggles to attract young people, while the aquaculture industry attracts young school leavers or graduates into entry-level work.

- The Victorian Seafood industry tends to be male-dominated with low percentages of women in the production sectors. However, in the processing sector, there appears to be a more equal gender balance.

- Fishing and fish farming require high skill levels. For example, successful skippers need to be efficient, productive, run a profitable business, have mechanical knowledge to fix and maintain their vessel and gear, be aware of market conditions, read the environmental conditions, and maintain relationships with crew and others.

The barriers to new entrants that have emerged over the past 20 years appear to be as a result of contraction and restructuring in the Victorian professional fishing industry. While interviews revealed there may still be opportunities for young people (e.g., as deckhands), the job may not be full-time work nor well-paid, and thus requires a second and flexible job to participate. The pathway to progressing through to owning an independent fishing business is also difficult, detracting from it as a career choice. The cost of entering the industry is now extremely high (e.g., licences and quotas) and the financial risks are high, with a pervasive sense of resource access insecurity currently in the Victorian industry due to government closures and restrictions. This is further compounded by the poor availability of financing to enter the fishing industry.

In their Aquaculture Development Plan for Western Australia, the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) address key issues that have previously presented barriers to developing the state's aquaculture. The Plan focusses on developing a robust industry that supports communities and helps diversify regional economies by creating new types of jobs, including opportunities for Aboriginal economic development and participation. When fully operational, current and proposed investments (such as the Albany Aquaculture Development Zone, which will be the largest single zone dedicated to marine shellfish farming in Australia) are projected to increase direct and indirect employment from an estimated 280 jobs to almost 6,000 jobs.

In the State of the North 2020 report, the Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia (CRCNA) estimates that there will be 1,400 to 2,300 new direct jobs in aquaculture over the next 10 years, while there is potential for a 50-fold expansion in area available for freshwater pond aquaculture. To meet these targets, the CRCNA advocates for increased training and skills development to promote aquaculture career pathways.

The Australian Seaweed Industry Blueprint: A Blueprint for Growth, by AgriFutures Australia, argues that Australia has the skill set to develop both seaweed cultivating and harvesting industries. This Blueprint offers a pathway to create a high-tech and high-value seaweed industry. The industry has the potential to be a $1.5 billion industry within 20 years due to its many possible uses, including for animal feed, fertiliser, pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals, as well as mitigating livestock emissions. It is estimated that, by 2025, the industry will employ 1,200 people, which could rise to 9,000 by 2040.

The NSW Land Based Sustainable Aquaculture Strategy highlights that sustainable seafood production to support future demands of food security for the state is a key focus of the New South Wales (NSW) Government. Aquaculture is a growing industry – NSW estuarine, marine and land based aquaculture is developing steadily. The aquaculture industry and the NSW Government are both conscious of ensuring that development of the industry proceeds in a manner that does not jeopardise its ecological sustainability and social licence. The following skills-related factors have been identified as key for success:

- The availability of suitably experienced and skilled staff or advisers, and/or access to appropriate training and instruction so an enterprise can run smoothly are essential to the success of an aquaculture business.

- Aquaculture like any business has potential pitfalls that may hamper the development of a strong business. Some pitfalls may include lack of 'business' experience or skills or lack of reliable and experienced workers and managers.

- Tank aquaculture often has higher capital and operational costs and requires skilled technicians to manage the system.

- Stocking density has a significant effect on the performance of aquatic animals. It influences behaviour, feeding patterns, incidence of disease, water quality and growth. Things to consider when calculating an appropriate stocking density include operator's skills and management systems.

For Australian fisheries to remain productive and sustainable (environmentally and commercially), there is a need to incorporate climate change considerations into management and planning, and to implement planned climate adaptation options. In the article An Assessment of How Australian Fisheries Management Plans Account for Climate Change Impacts, the authors investigated the extent to which Australian state fisheries management documents consider issues relating to climate change, as well as how frequently climate change is considered a research funding priority within fisheries research in Australia. Results show that commercial state fisheries management documents consider climate only to a limited degree in comparison to other topics, with less than one-quarter of all fisheries management documents having content relating to climate. There is a clear need for fisheries management in Australia to consider longer-term climate adaptation strategies for Australian commercial state fisheries to remain sustainable into the future. The authors suggest that without additional climate-related fisheries research and funding, many Australian agencies and fisheries may not be prepared for the impacts and subsequent adaptation efforts required for sustainable fisheries under climate change.

Fisheries are under threat from climate change, with observed impacts greater in faster-warming regions. In the article Stakeholder Perceptions on Actions for Marine Fisheries Adaptation to Climate Change, the authors investigated current and future potential for climate adaptation to be integrated into fisheries management strategies using Tasmanian commercial wild-catch fisheries as a case study, and then identified obstacles and recommendations for fisheries management to better adapt to future climate changes. The research found that climate adaptation in Tasmania fisheries management has largely been passive or incidental to date. A more forward-thinking and proactive response to climate change for Tasmanian fisheries, as well as a more flexible and resilient fishing industry that is better able to absorb shocks related to climate change, is needed.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report Adaptive Management of Fisheries in Response to Climate Change, aims to accelerate climate change adaptation implementation in fisheries management throughout the world. It showcases how flexibility can be introduced in the fisheries management cycle in order to foster adaptation, strengthen the resilience of fisheries, reduce their vulnerability to climate change, and enable managers to respond in a timely manner to the projected changes in the dynamics of marine resources and ecosystems. The publication includes a set of good practices for climate-adaptive fisheries management that have proven their effectiveness and can be adapted to different contexts, providing a range of options for stakeholders including the fishing industry, fishery managers, policymakers and others involved in decision-making.

The Seafood industry is currently regarded as the most dangerous work sector in Australia. The article Joint Action to Tackle Safety, outlines new strategies, underpinned by research, that show how shared approaches can improve safety in the industry. Research has found that traditional approaches, including training and regulation, were failing to improve safety practices because they often failed to recognise the specific needs of a particular fishery or operation. In response, the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) has moved to address gaps in the available first-step training resources, which can be tailored for specific fisheries. Its SeSAFE program provides basic, accessible training modules that cover both industry-wide issues such as 'man' overboard or sun-safe practices, and industry-specific requirements such as boom safety on prawn trawlers. Modules have been co-designed with industry and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), or adapted from other industry programs, including a significant contribution of training material from Austral Fisheries. The time required from skippers or business owners is minimal; they just need to select the modules they want their staff or crew to do. The training provider can then coordinate the training on their behalf. Each module can be completed in 10 minutes or so. They are available online or offline, formatted for computers and tablets, and optimised for mobile phones. Challenges to uptake include a reluctance by crew to do the training, often coupled with a shortage of crew. This can make it harder for skippers to insist, or to remain committed to continually repeating training in the face of high staff turnover.

Levels of psychological distress among fishers have been found to be twice that reported in other industries. Factors included the 'traditional uncertainties' of weather, oceans, fishing and markets, and 'modern uncertainties' related to the regulatory environment, industry reputation and community support. Initiatives focused on mental health include:

In August 2021, the media release Navigator a Boost to Sea Training and Jobs, announced that the new training vessel, The Navigator, has been officially commissioned for Seafood and Maritime Training (SMT) and is set to provide more hands-on skills and qualifications for Tasmanian learners. The Navigator will be used to train students across a range of maritime disciplines including maritime operations, aquaculture and seafood processing qualifications. With more than 1,500 students enrolling with SMT each year this new training vessel will make a significant difference to both students mastering their new careers and the maritime and seafood industries in need of work-ready skilled team members. Having served Tasmanian learners and the sector for 35 years, SMT is recognised as Australia's leading seafood and maritime industry training provider and this is the largest single investment SMT has ever made. It will take their ability to shape careers and provide a pipeline of highly skilled workers to the next level, and shows there is a high level of confidence in demand for training in Tasmania. The Tasmanian Government supports SMT in training Tasmanians for rewarding careers through their Apprentice and Trainee Training Fund (User Choice), Skills Fund, Train Now Fund and the JobTrainer Fund. Notably SMT delivers traineeship training in Certificate III in Aquaculture through the Apprentice and Trainee Training Fund (User Choice) which alone currently supports nearly 150 trainees.

The National Skills Commission's Skills Priority List: June 2021, lists the occupations of Master Fisher, Fishing Hand and Deck Hand as having 'Moderate' future demand and the occupation of Aquaculture Farmer as having 'Soft' future demand. Research has identified some difficulty filling vacancies for these occupations across Australia. There is a shortage of Master Fishers and Deck Hands in the Northern Territory, Fishing Hands in Western Australia, and Aquaculture Farmers in New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania and the Northern Territory.